What is the “35mm equivalent”?

The term “35mm equivalent” in cinematography refers to a way of standardizing the field of view across different cameras and lenses to match the perspective seen through a standard 35mm film frame. It is particularly useful when comparing cameras that have different sensor sizes.

There are so many questions that are a direct result of this definition:

- Is understanding the 35mm equivalent even useful practically?

- What is the standard 35mm film frame for cinematography? Aren’t there many standards?

- Why and when do we even need to compare camera sensor sizes and lenses?

- Is this the same as “full frame equivalent”?

Let’s tackle this head on.

Why do we need an “equivalent” at all?

When you compare two things, one of them will typically be a “standard”, a known quantity.

E.g., when you travel internationally, you’ll be faced with the prospect of finding the equivalent rates of the foreign currency to your local currency, so you know exactly how much you’re spending. In this scenario, the “standard” is your local currency, the one around which your whole life revolves.

With cameras, we have different sensor sizes. There are full frame sensors (36mm x 24mm), APS-C sensors (e.g., 22.3mm × 14.9mm among others), Micro Four Thirds sensors (7.3mm × 13.0mm) and so on.

Every camera needs a lens in front of it. Sometimes, you can use a lens designed for one sensor on another sensor. This is where the equivalent has its genesis. How can you tell what you’re going to get when you fit a lens made for one sensor on a camera body with a different sensor size?

Think of windows. A larger window will show more scenery than a smaller one. Yet, the focal length of your eye remains the same. Sensors behave like windows.

A larger sensor will always show you more scenery than a smaller one.

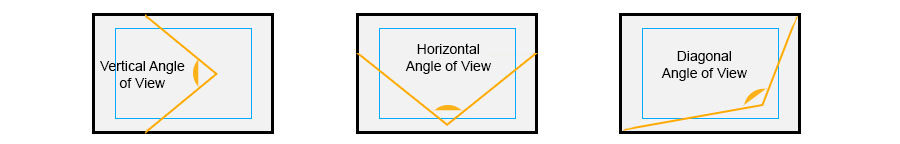

Now, there are three ways to measure the scenery projected on a sensor:

Depending on how you use your camera, you might find yourself preferring one of the three. The outer box is a larger sensor, while the blue outline is the smaller one. Even though the angle from the lens is the same (which is dictated by its focal length), the ‘projection’ changes. Parts of the scene are cut off in the smaller sensor.

E.g. let’s say a 50mm lens on a full-frame camera (sensor size: 36mm x 24mm) covers a scene in this fashion:

- Horizontal angle of view: 39.6o

- Vertical angle of view: 27o

- Diagonal angle of view: 46.8o

Now, let’s say someone (an evil cinematographer) uses a lens made for this sensor on a smaller sensor, say, APS-C, which has a sensor size of 22.3 × 14.9 mm.

Parts of the scene that were visible with a full-frame sensor are now cut off. The evil cinematographer shows you the final image, but lies to you and says it was shot on a full frame sensor.

He asks you to guess the focal length. Using a bit of simple trigonometry (or better yet, experience) you arrive at the conclusion that an 80mm lens was used. The lens used was a 50mm, but the same lens on an APS-C sensor gives the approximate equivalent of an 80mm lens on a full frame sensor.

In other words, you’d get what you were shown by the evil cinematographer with an 80mm lens on a full frame sensor.

Here’s another way this information is helpful: Let’s say you have two camera bodies dangling around your neck – one a full-frame camera and another a Micro Four Thirds camera. Here’s a real life scenario: You want to shoot the exact same scene with both cameras.

You shoot first with the full frame camera using a 24mm lens. If you use a 24mm lens on Micro Four Thirds you don’t get the same image. It appears severely cropped. You try a wider lens, let’s say a 21mm. It’s better, but still cropped. Then you go wider, and wider, until you finally put on a 12mm lens.

Now you’ll see the same scene. This is how the lens equivalent works.

So, to answer the question: Why do we need an “equivalent” at all?

We need an equivalent because adapting lenses to different standards is a common feature in cinematography. Here are some typical scenarios:

- There are different 35mm standards in cinema: Academy, Super 35mm Flat, Super 35mm Scope, etc. However, the lenses are made to cover all of these formats.

- Full frame cine lenses can be used on Super 35mm and 16mm-type sensors.

- With mirrorless camera systems, you also have the usage of full frame camera lenses on APS-C sensors, various flavors of Super 35mm, Micro Four Thirds and so on.

Therefore, it is important to understand how to properly calculate the equivalent. Stick around, I’ll help you with it.

Problems with the “equivalent”

One of the problems with the 35mm equivalent is that people tend to look for perfection. They say things like: “The focal length doesn’t change from one sensor to another.” Such statements conflate a truth (focal lengths don’t change) with an incorrect context. They simply don’t have the real world experience required to understand which parts of the 35mm equivalent are useful and which aren’t.

In fact, looking for the exact equivalent is a fools errand. Here are some factors that make it so:

- Not only are sensor sizes different, but they might have different aspect ratios. So, the equivalent along one dimension (say, horizontal) will not translate into the equivalent on another (the vertical), and so on.

- Sensors are not always precise. E.g., sensor A can have a horizontal size of 36mm, while sensor B, also classified a full frame sensor, has a horizontal size of 35.9mm.

- Lenses are not always precise! A 50mm lens from brand A might not have the same field of view of a 50mm lens from brand B.

Therefore, whenever you’re looking for equivalent lenses, getting a rough idea is enough.

The only way to know for sure if the lens will work for your scene is to use it.

Any cinematographer worth their salt will test things first. After all, cinematographers ought to select sensors and lenses for emotional impact, not mathematical accuracy.

Whose 35mm are we talking about here?

Now it’s time to answer the second question: What is the standard 35mm film frame for cinematography? Aren’t there many standards?

The title of this article asks: Why is it confusing? ‘It’ here does not refer to ‘equivalent’, which is simple enough to understand. It’s for the other word: ’35mm’.

It’s like saying ‘dollar’. What do you mean: American, Australian, Singaporean, Namibian? Similarly, for better or for worse, there are two kinds of 35mm in the world of cinematography:

- 36mm x 24mm, simply known in the photographic world as 35mm or full frame. Unfortunately, companies like Arri now refer to this size as Large Format. It’s bananas.

- Super 35mm, which has multiple standards:

- Academy – 22mm (1.375:1)

- Widescreen – 21.95mm (1.85:1)

- Cinemascope – 21.95mm (2.39:1)

- Super 35mm 3-perf – 24.89mm (16:9, 2.39:1)

- Super 35mm 4-perf – 24.89mm (4:3)

- There’s also anamorphic, but let’s not go there in this article.

There are people who think one should use Super 35mm when calculating the 35mm equivalent. After all, for cinematography, why should anyone consider a standard photographic sensor size anyway?

The answer: Because it is the only one true standard.

Super 35mm standards are a relic of the film era. In the digital camera world, even if sensor manufacturers use the term ‘Super 35mm’, they don’t actually mean the film size that it refers to. Here are the horizontal sensor lengths of a few modern cameras:

- Arri Alexa 35 – 28mm

- Arri Alexa Mini – 28.5mm

- Red V-Raptor S35 – 26.21mm

- Sony Venice 2 Super 35mm frame – 24.3mm

- Blackmagic Design URSA G2 – 23.1mm

- Canon C300 Mark III – 26.2mm

They all claim to be Super 35mm! Which of them is true to that?

See for yourself. Here’s a diagram comparing the two versions of Super 35mm:

The standard Super 35mm width is exactly 24.89mm.

Not a single manufacturer makes the exact same size as Super 35mm 3-perf. See the problem?

There is no single standard for Super 35mm today in digital cinema cameras.

Cinematographers, traditionally, never use the term ‘full frame’ unless they’re looking for a fight. They also don’t use the term ‘Super 35mm’ by itself simply because there are different versions like 4-perf, 3-perf, 2-perf and so on. They would have to get more specific than that.

Some cinematographers prefer anamorphic exclusively, so what would ‘full frame’ or ‘Super 35mm’ mean to them? Nothing.

Super 35mm, then, is a term ‘up for grabs’. Digital camera manufacturers have taken advantage of this ambiguity and you can see the result for yourselves.

To make my life (and yours) easier, I use the “full frame” 35mm size of 36mm x 24mm when calculating the ’35mm equivalent’ or ‘full-frame equivalent’. Here are my reasons:

- Full-frame 35mm is a very old standard that hasn’t changed in about a century.

- It is extremely common and refers to a fixed size and aspect ratio, both horizontally and vertically. There is no ambiguity.

- The full frame 35mm size is uncorrupted by unscrupulous marketing.

- Photography cameras are ubiquitous.

- Modern cinematographers also frequently film with full frame mirrorless cameras.

- Traditional cinematographers often shoot stills, so they know what full frame 35mm means.

- Lens manufacturers have made cine lenses that cover this larger area.

Therefore, for the sake of world peace, when I say “35mm equivalent”, I am referring to a 36mm x 24mm frame.

No exceptions.

So, to answer the fourth question before the third one: Is this the same as “full frame equivalent”?

Yes, since full frame 36mm x 24mm is the only standard everyone agrees on in this day and age, it’s best to base your 35mm equivalent calculations on the 35mm full frame sensor.

Therefore, as far as I’m concerned, 35mm equivalent and full frame equivalent are the same for all practical purposes.

Why and when do we even need to compare camera sensor sizes and lenses?

Today more than ever we need to calculate the approximate change in angle of view with a particular lens and sensor combination.

E.g., let’s say we are filming with an Arri Alexa 35 and Arri Master Prime lens set for a project. After the project is complete you want to use the same lens set, but now on a Red V-Raptor S35.

You put on a 32mm, say, to test.Your attention is drawn to the fact that you don’t get the same frame. In fact, it’s a bit cropped.

The lens focal length does not change (purists, stand back!) of course, but the equivalent focal length is now 26.21/28 x 32mm = 30mm.

If you’re using the same lens set on a Blackmagic Design URSA G2, the equivalent focal length is now 23.1/28 x 32mm = 26mm

See the problem? You don’t get the same frame when the camera is in the same distance away from your subject.

So, why not just step back a bit to get the equivalent frame?

It’s a valid question, but not always possible in filmmaking. Sometimes, you’re already at the end of the room and there’s no room to step back. You don’t want to find out after you’ve wasted everyone’s time on set. Films are expensive on a per minute basis.

Other scenarios are when you need to mix and match formats for stunt scenes or in multi-cam setups, or if you’re using slow-motion cameras or drone cameras, etc., for special shots.

As a cinematographer you’re trying to present a unified world for your story. You need to be in control of the visual, and part of this is to understand and utilize the 35mm equivalent.

Now watch this video:

14 replies on “What is the 35mm Equivalent and Why is it Confusing?”

Great info! One of the few thorough discussions of the topic on the internet.

I have a question about crop factor in regards to cinematography. I know, I know, this again! I am left with one aspect of it that I’m not clear on.

I’m using a camera with a 4/3″ sensor. I’m learning cinematography from literature and videos, reading about techniques, interviews with directors, etc.

Say I want to emulate the field of view look of a specific film, and I read that the director (let’s say Scorsese) used only one specific lens for the entire movie, he says he used the 28mm the entire time. As usual, no mention is made of sensor size. (Actually, most of these are older movies that used actual film so I’m unsure if they even use sensors or if the image is captured directly onto the film). My question is this: Should I be assuming he is meaning 28mm in the sense of a Super 35 3 perf sensor and I should match the crop factor to that to achieve the same field of view? (I know other factors won’t match such as depth of field.) This would be ~1.44 for MFT (horizontal) so that would be about 20mm.

Whenever I hear a director talk about what lens they used for a shot, or an instructor about what specific focal length to use to achieve a specific shot, should I be assuming they mean with a “standard” Super 35 3 perf capture size and I should adjust in my mind the relative MFT lens that means? Or does the sensor size and/or cropping vary so much throughout a movie’s shooting and between movies that a director talking about what lens he used is useless information, other than you roughly knowing it was wide, normal, or telephoto?

I know I can just frame a shot how I want and in the way it calls for, but it would be nice to know for learning’s sake.

Nice

Either I’m not getting something, or this article is totally confusing still photography and cinema terminology.

The standard for 35mm still photography has been an exposed area of 24 X 36mm since the early days of Leica.

The standard for cinematography, turns that image on its side, using less than half the area of stills.

If you want to equate the two uses of 35mm stock in the same manner, you need to reference the VistaVision, double frame, horizontal standard, which exposes the entire 24 X 36mm frame horizontally, and then cropping to any number of different aspect ratios, but most nominally, 1.85, for either horizontal large format projection, or via reduction printing to standard vertical 35mm format.

While one might reference 24 X 36 as standard full frame, the term is correct for still photography ONLY, and has no reference to cinema.

“The standard for cinematography, turns that image on its side, using less than half the area of stills.” Not really. I choose to form my own definitions, and do not agree with your statements.

You have an absolute right to define the world in your own way, but attempting to force that definition on an industry with technical standards is not helpful.

By your definition, every film produced before 1954 never happened, and that all of cinema began with Strategic Air Command.

Were Intolerance, Gone With the Wind, Casablanca and The Godfather not photographed full frame?

A simple definition of Full Frame in cinema, is an image exposed vertically from perf to perf on standard 35mm stock, with a frame line separating frames, every four perforations.

I think you have misunderstood the intentions of the article. Also, cinema never had one constant “full frame”. It was constantly evolving, and never was realized into one exact standard. By the way, this ‘confusion’ was ‘forced on an industry’ by people who didn’t really much care about the industry in the first place. Maybe you should ask them why they never defined their terms and came to a universal agreement.

And your own views on full frame are limited to Hollywood. There’s a huge movie-producing world outside Hollywood as well. The rest I’ve explained in the article. You’ve made your point.

“A simple definition of Full Frame in cinema, is an image exposed vertically from perf to perf on standard 35mm stock, with a frame line separating frames, every four perforations.”

That is correct as a definition not the rule.

BTW cinema did not born on Hollywood. France did it. And they not used 35mm… :D

combridge Thanks for sharing!

A good explanation of a much misunderstood subject. As a Cinematographer of 40 years ( 2/3 of which was film) I would like to expand on your excellent ‘side bar’ article of Cinemascope AR. Your conclusion is technically correct correct, 2.39.1 is the gold standard, but, back in the day the only AR we worked with was ‘2.35:1’ only because we had to allow for the optical sound track and if we didn’t the optical production house would be greatly displeased as it meant them having to make a shift in the optical centre of the projected image. Not an inexpensive or quick process on a feature in the days before computers. You’ll find most release prints from the ‘scope era are all 2.35:1 Just a bit of trivia, I look forward to future articles. Cheers

Sareesh Sudhakaran ryleee Thanks Sareesh, i like this article because it presents an overall look at digital standards without getting bogged down in details. I’ve bookmark it for future reference.

ryleee Thanks a lot for catching the error. I have corrected it. It is now 12mm instead of 48mm.

To answer your question about S35, the official standard is 16:9, but neither widescreen nor anamorphic DCI conform to 16:9, so people use masks to get 1.85:1 or 2.39:1. There’s no error, the ‘standard’ is confusing by definition.

There seems to me (a novice at calculating lens size) there are some glaring errors in this blog, In the comparison of a full frame and a Micro Four Thirds the use of 24mm vs 48mm lens should be reversed. Also, comparing lens sizes, Super 35mm 3-perf – 24.89mm (16:9, 2.39:1) suggests two widely different aspect ratios for the 35mm 3-perf industry designation. Are there other errors . . .

brawlster LOL…but who would understand me then? In the digital world, even ’35mm’ or ‘135’ does not exist, because there is no film border or perfs at all!

‘Super 35’ was always okay, when it was on film. Now it has jumped out of its skin and can be anything!

Maybe you could just call “full frame” what it actually is. 135.

And super 35 could be…super 35 The three and four perf versions are the same width and the digital cameras are all very close.

JB